Native and First Nation tourism is surging across North America – and one of the driving forces behind the movement is the revival of ancient Indigenous trails as modern routes for hiking, cycling and rafting.

In May 1877, Chief Standing Bear of the Ponca Tribe and his people were forcibly marched more than 500 miles from their homeland in Nebraska to “Indian Territory” in present-day Oklahoma. Escorted at gunpoint by the US Cavalry, the journey came too late in the year to plant crops. The resulting winter was devastating: one-third of the Ponca died, including Standing Bear’s son and daughter, while many survivors were left sick or disabled.

Honouring his son’s final wish to be buried in Nebraska, Standing Bear returned north, only to be arrested for leaving the tribe’s newly designated reservation. In a landmark 1879 court case, he argued that Native Americans were persons under US law and therefore entitled to basic rights. The judge agreed, ordering his release in a ruling that reshaped Native American civil rights.

Today, that history echoes across the landscape.

Standing in the town of Beatrice, Nebraska, I walked along the Chief Standing Bear Trail, a 22-mile limestone path following the bends of the Big Blue River. Once a network of Indigenous hunting and trading routes, it later marked the beginning of the Ponca’s forced removal. As the trail wound past farmland and trees, it was impossible not to imagine the weight of that journey.

The story of the Ponca highlights a reality often overlooked: many of the trails Americans hike and bike today were first carved out by Indigenous peoples centuries ago. As Native lands were seized, governments repurposed these routes into roads and railways. Portions of the Ponca’s Trail of Tears, for example, later became part of the Union Pacific railway.

Now, tribes, states and organisations such as the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy are transforming these corridors once again – this time into recreational routes that reconnect people with Indigenous history.

Chief Standing Bear Trail traces ancient Native American paths and is now a hiking and biking trail (Credit: Brandon Withrow)

Chief Standing Bear Trail traces ancient Native American paths and is now a hiking and biking trail (Credit: Brandon Withrow)“All these trails were here before,” said Judi gaiashkibos, executive director of the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs and a member of the Ponca Tribe. “Most of the trails used for slow tourism today were originally ours.”

The Ponca now hold the deed to the Chief Standing Bear Trail, where interpretive signage tells their story. Gaiashkibos hopes visitors will come “to hear new stories, slow their lives down and reconnect with the land”.

That reconnection is fuelling a booming industry. Indigenous tourism generates an estimated C$3.7bn annually in Canada, while Native tourism in the US is valued at $15.7bn. Tribes are increasingly centring tourism around their strongest assets: land, culture and storytelling.

In Washington State, the nearly completed 135-mile Olympic Discovery Trail has emerged as a major non-motorised tourism draw. Stretching from Puget Sound to the Pacific Ocean, the route winds through temperate rainforests, glacial lakes and mountain vistas. While built atop a former railway, it began as a footpath linking Indigenous villages.

One of those communities is the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe. Today, the trail passes through tribal land, including the tribe’s North Campus and 7 Cedars Casino, with educational signage and a Native Art Gallery showcasing Indigenous artists.

The route also runs alongside the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribal Library. “We’re creating exhibit spaces that allow the tribe to tell our story from our own perspective,” said Luke Strong-Cvetich, the tribe’s planning director.

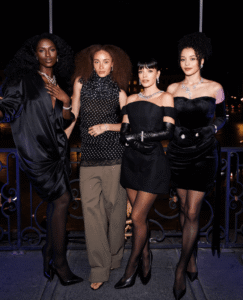

Indigenous tourism has been surging across the US and Canada (Credit: Juliana Swenson/Alamy)

Indigenous tourism has been surging across the US and Canada (Credit: Juliana Swenson/Alamy)Along the trail, the tribe is restoring salmon habitat and reclaiming polluted land. The expanded Dungeness River Nature Center now serves as both visitor centre and educational hub focused on conservation and the tribe’s relationship with the river – a vital salmon habitat relied upon for thousands of years.

In Idaho, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe is also using slow tourism to reclaim both land and narrative. Their ancestral territory once spanned five million acres across Washington, Idaho and Montana. By the early 20th Century, allotment policies had reduced it to just 345,000 acres, while highways and railways replaced traditional trade routes.

When the Washington & Idaho Railroad shut down, it became the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes, a 72-mile paved cycling path. The tribe now oversees 15 miles of the route, integrating it into the Coeur d’Alene Casino Resort’s cultural tourism programme.

Visitors can join guided hikes along ancestral trails, kayak and canoe with tribal guides on Lake Chatcolet, or cycle the route on Indigenous-led excursions, with bikes provided.

“We don’t have a traditional cultural centre,” said Wasana McGowan, who manages cultural tourism at the resort. “So we use the land itself. The reservation is our classroom.”

In the American Southwest, many travellers are familiar with Grand Canyon National Park. Fewer know about Grand Canyon West, located on the Hualapai Nation reservation. Here, visitors encounter the same vast canyon walls – along with the dramatic Skywalk, a glass bridge extending 70ft over the canyon edge, owned and operated by the Hualapai.

The Olympic Discovery Trail was originally a foot trail connecting Indigenous villages (Credit: Spring Images/Alamy)

The Olympic Discovery Trail was originally a foot trail connecting Indigenous villages (Credit: Spring Images/Alamy)Guests can hike, zipline across side canyons, or meet cultural ambassadors who share Hualapai history. A self-guided app offers videos, interviews and maps that deepen the experience.

“Most visitors know very little about the people or the land they’re standing on,” said Loretta Jackson-Kelly, supervisor of the Grand Canyon West ambassador programme. “We’re here to share that history.”

But the heart of Hualapai tourism flows below the canyon rim: the Colorado River.

For centuries, the river connected tribes and trade routes and remains central to Hualapai identity and creation stories. Its curves once marked the boundaries of a seven-million-acre homeland. Gold discoveries in the 19th Century changed that, as mining claims fractured the land and restricted access until the tribe secured a reservation in 1883.

Today, Hualapai River Runners lead rafting expeditions through the canyon, combining adventure with cultural storytelling and guided hikes to sacred sites.

“The Hualapai people are incredibly proud to share their backyard,” said Jackson-Kelly. “One of the world’s great wonders – the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River.”

Through tourism, ancient trails, rivers and landscapes are once again becoming pathways for Indigenous voices – restoring history not as footnotes, but as living journeys.